Blazing a Trail Into Retail’s Future

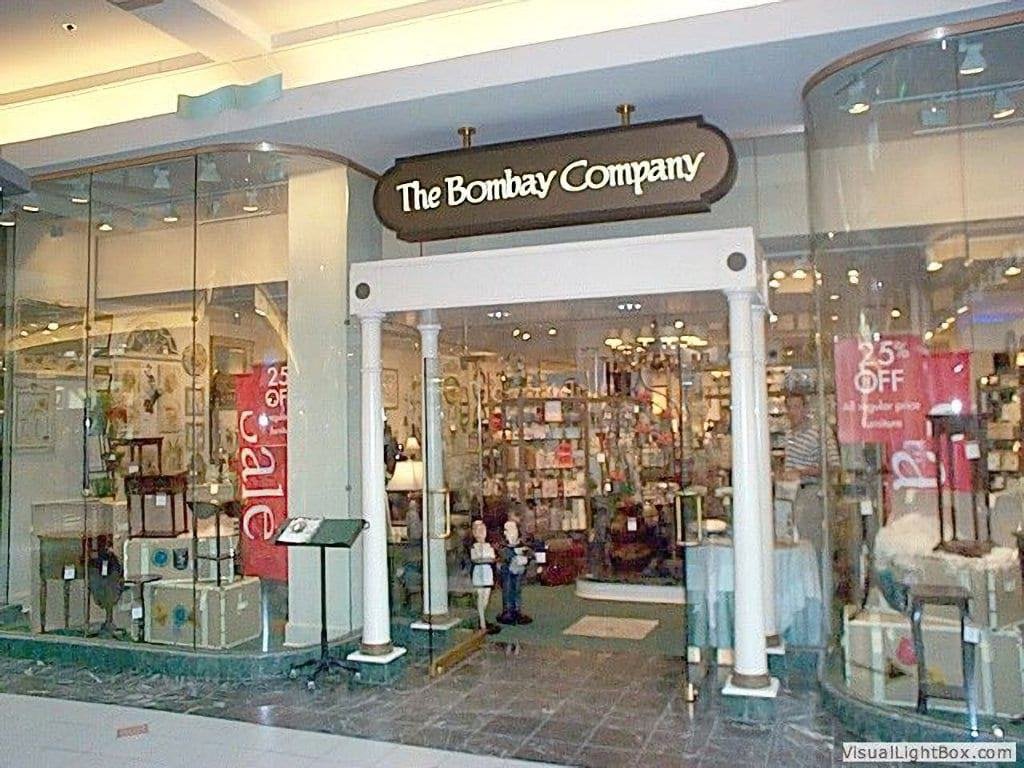

It’s late afternoon in the early fall of 1995, and I’m staring out the window of my corner office facing west, watching another amazing Texas sunset. As the Chief Information Officer of The Bombay Company, a popular mall-based specialty retailer of home furnishings and wall decor, it was my job to envision how technology would shape the company’s future. And I was good at it. I discovered my future in 1983 when I convinced my Dad to part with five grand ($13K in 2021 dollars) for an original IBM personal computer. I knew it was a big ask – that’s a LOT of money – but he was motivated by the passion that consumed me when I described how personal computing would change the world. My vision was so clear that I took bold risks to ensure that I was influential in shaping its fruition. I’d caught the face of the most significant technology wave in history and hung ten off the top to my dream job here in Ft. Worth. I’d seen incredible things during that twelve-year ride, but nothing compared to the epiphanic rush that coursed through my veins in the burnt-orange haze of that fall evening.

I’d just discovered the internet and could vividly see the future of retail, and instantly knew that nothing would ever be the same.

Being Visionary is a Double Edge Sword

The biggest problem with being a vocal visionary is trying to convince the people in your life that you’re not certifiably insane. Everyone can see the future when it smacks them in the face. But trying to describe it to those who preferably live in the moment is a daunting task, and would be more complicated than it’s worth if it wasn’t part of your job description. For the second time in my life, I could undeniably see technology’s future six to ten years down the road. And like before, I didn’t think it would happen; I knew it would happen. That’s pretty cool for a CIO since most people in that job endure a constant conundrum: You make a lot of money to envision technology’s future in a zero-sum game. If you’re right, you’re a “visionary” hero, but you lose your job if you’re wrong.

Sometimes It’s OK to be Second Best

Most CIOs play it safe and mitigate their risk, which is good for them but bad for their company. I’ve known a handful of visionary CIOs in my thirty-four-year technical career. We all shared the same attributes: an undeniable passion for technology, the ability to predict its future accurately, and the confidence to act on our instincts. Best-in-class CIOs are visionaries with the skill to successfully navigate political crap. I wasn’t a best-in-class CIO because I couldn’t stand political crap. I still can’t. It almost killed me at Microsoft – literally. I’ve never played it safe in my career because I can’t ignore something I can see with absolute certainty. I instinctively act. My vision was clear, so act I did, right into an exhilarating hailstorm of political crap.

The Power of Passion

My boss at the time was a delight to work for and a fantastic mentor, teaching me much of what I know about the retail industry. Jim Herlihy is a financial genius, a blue-collar kid from New Jersey who made it big by taking The Bombay Company public in 1993. He was maybe five feet, five inches tall, talked just like Thurston Howell III, and incredibly witty – but he stuck out like a sore thumb within the crusty walls of the elite social circles in Ft. Worth. Jim barely understood a word I said about technology as it made his head swim. But he was impressed with my passion for it.

You can’t fake passion. People are instinctively drawn to it like mosquitoes to a bug zapper because it’s so rare. Energized by my newfound discovery, I sprinted into his office one morning with an offer he couldn’t refuse. “Give me $250,000,” I said with complete confidence. “Just the cost of opening one store. In return, within a year and with no additional headcount, you’ll get the most profitable store we have”. And for the deal closer, I threw in: “this store will be available to everyone in the world, twenty-four hours a day,” I proclaimed as if that should make sense to any seasoned retailer at the time. Let’s just say I “miscalculated” his response.

He held that classic “waiting for the punchline” look for about a minute. Then he burst out laughing, asked me if I was serious and how that was even remotely possible.

Conviction Separates the Men from the Boys

Before he could finish asking, I was already at his whiteboard, sketching out web hubs, domain names, and internet service providers. His laugh faded to a grin as he obliviously watched me map out out the future of retail. He was clueless but quite intrigued. I was explaining this as if it had already happened. He knew it took guts to make such a claim. And my passionate conviction was disarming. Then he said the same thing I’d heard from my father a decade before – “I’m not quite sure I understand what you’re talking about, but I believe in you.” Hearing that was motivating and exhilarating – both times. He explained that only the board of directors could approve such a sizable investment but that he would back me and get me on the agenda of the next board meeting to solicit the funds.

Passionately Misguided

The board meeting took place in the spring of 1996, and as promised, I was on the agenda. The board comprised seven seasoned industry veterans from their late sixties to early eighties. None of them knew anything about technology other than we were expensive and apparently “invaluable.” I gave my best executive pitch, boldly predicting retail’s future to these nostalgic retailers. I showed them the only retail websites that existed then, including Amazon (huh), eBay (who?), and Burlington Coat Factory. Only Amazon and eBay offered products for sale, something I confidently proclaimed we could do, and in time for the 1996 holiday season. I’ll never forget the dead silence and bewildering stares that welcomed the end of my presentation. In their minds, I was passionately misguided. Retail didn’t work that way, at least within their tenured paradigm, but they humored me and asked that I leave the room while they “considered it.”

The Retail Prophesy of the Century

Five minutes later, they handed down their verdict. I’ll never forget that moment as long as I live. The board chairman politely congratulated me for having the confidence to make such bold claims. While they didn’t specifically say the scenario was improbable, these non-technical retail sages made their prediction about “this internet thing”:

“We’re quite impressed with both your passion and confidence in this ambitious vision, Mr. Gruehn. The board, however, is convinced that “this internet thing” is a fad. Similar to the CB radio craze in the ’70s. It will similarly fade into obscurity when its mystique loses its temporary appeal,” the chairman matter-of-factly prophesied.

I was stunned – flabbergasted, actually. How could something so obvious, so incredibly game-changing, be compared to a CB radio? I blatantly stared down each board member in turn, but it was evident that their minds were made up – except for one. Robert “Bob” Nourse was the CEO and entrepreneurial retail genius who first saw Bombay’s potential. He invested $125,000 of his own money and borrowed an equal amount from a bank to get the company started, ironically the exact amount I requested. Bob looked at me, intrigued. I didn’t feel that he thought I was right, but I instinctively felt he wanted me to be right. That’s the only encouragement I needed. I would prove to him, and all of them, that I was, in fact, right.

The Perfect Scenario

The Bombay Company had the perfect infrastructure in 1996 to launch a web store capable of selling products in a matter of months. They had approximately 560 stores, but more importantly, they had a thriving catalog business, which would become the fulfillment center for all my web orders. Their catalogs would provide a rich pool of high-resolution digital product images required for the website (digital image creation and scanning was an expensive endeavor in the early 90s). While sales outside the country were rare, I verified that they did happen and that the call center could handle them. I just needed a website to post the images and take orders, which would be emailed directly to the call center as if a customer had called them in.

Ask For Forgiveness Later

Notwithstanding the board meeting, this vision was moving forward. But I was staring at a rock and a hard place. My conviction wouldn’t allow me to accept defeat, but I had no money to proceed. My initial request contained a ton of contingency buffer, and I assumed I’d use professional web developers, both rare and expensive at that time. But passion and necessity are the mother of invention. Upon further investigation, I was confident I could get an initial “bare bones” website up and running for $45,000 to $55,000 in four weeks. The only issue was that I hadn’t “officially” been authorized to launch the site, but I considered that a minor detail. It wouldn’t be the first or last time I acted on instinct and asked for forgiveness after the fact. I quietly “reallocated” the base money from within my authorized annual budget, contracted a reputable Internet Service Provider who set up and configured the server and connectivity, and pondered how I could get the site built under the radar. If this were going to happen, I’d have to build it myself.

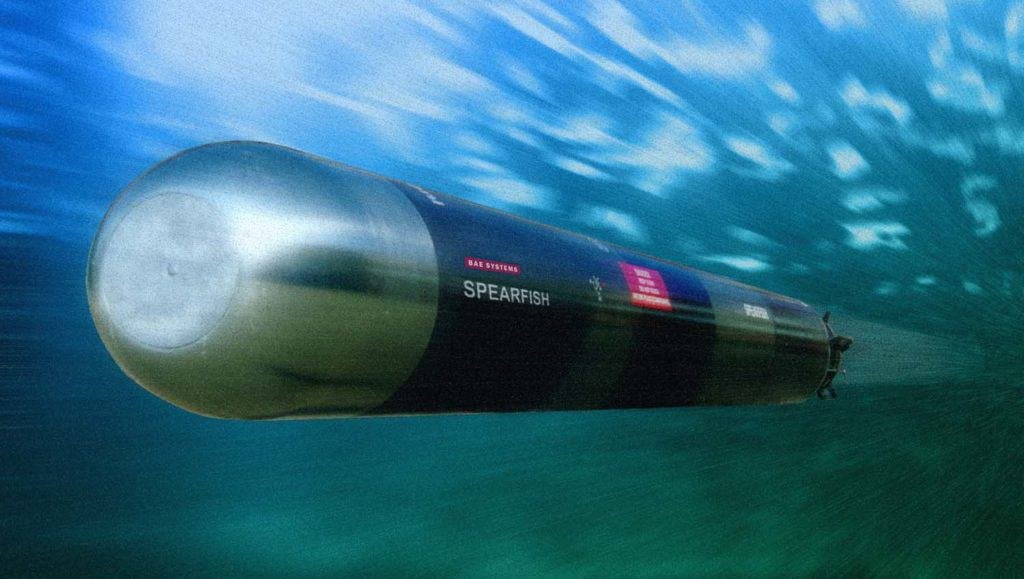

Damn the Torpedoes

Late one Friday on a warm summer day in 1996, just two months after the infamous board meeting, I embarked upon a mission to make my vision a reality. Failure was not an option, and I willed myself to become a web developer and take The Bombay Company online single-handedly.

I was motivationally terrified.

I’d already invested tens of thousands of unsanctioned dollars in a stealth project that my board associated with a “fad.” While I fervently believed that what I was doing was in the company’s best interest and incredibly ahead of its time, I knew full well that failure could result in termination. Not to mention a pretty severe “blemish” on my otherwise stellar professional track record. But I believe that your life is the summation of the decisions you make along the way. I would never have forgiven myself if I passed up such a game-changing challenge, only to see some other visionary with bigger cojones grab the opportunity. I channeled my fear into faith in myself. I had the confidence to believe in something I hadn’t yet created but knew I would. Then I let it go and got in “the zone.”

On my way home, I quickly stopped at the local bookstore (remember them?) to pick up HTML and website development books, made an excessive amount of coffee, and boldly charged into retail’s future.